Efforts to promote hygiene and prevent disease date all the way back to ancient civilizations. People of the past might not have understood specific scientific mechanisms behind plague or smallpox, but it was pretty obvious that A) Something’s killing everybody, and B) Maybe let’s avoid it. Obviously, over time, awareness of health changed. Often, it was intentionally influenced by scientists, governments, and, eventually, marketers. We dove into the history of modern Public Health campaigns to see how their messaging differs from our own behavioral change campaigns.

Diseases

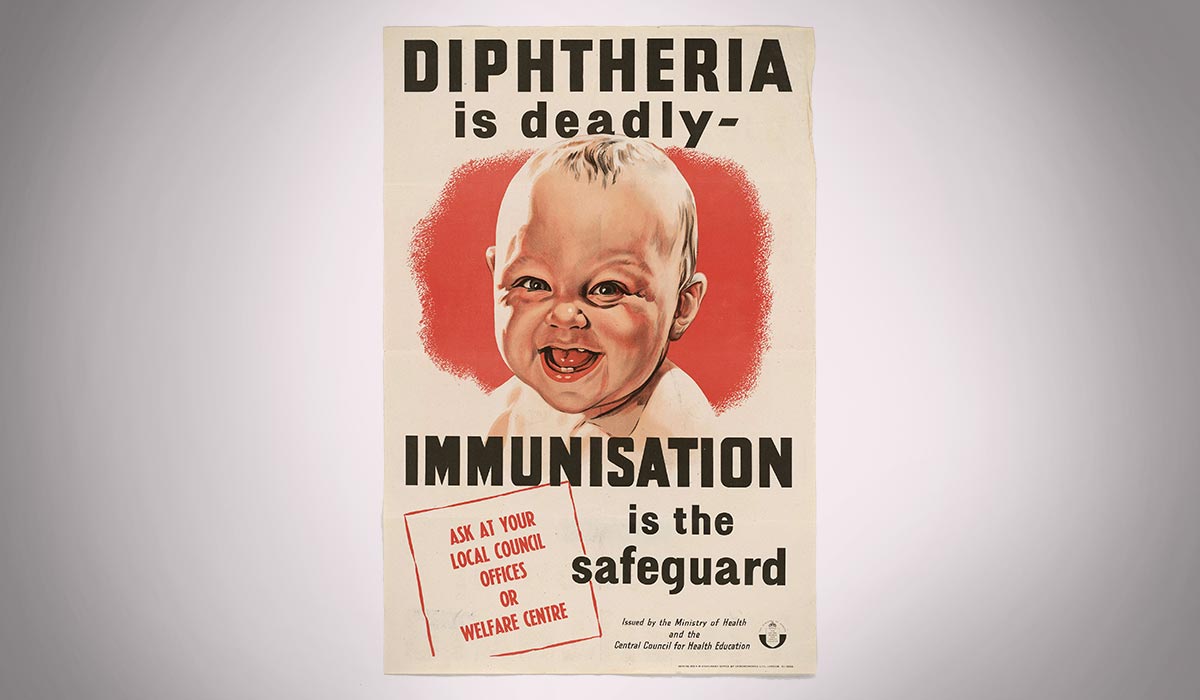

Since the first thought people have when hearing about a deadly new disease is something like, “I’d rather not die from that, thanks,” many 20th Century campaigns pretty straightforwardly tapped into fear as the motivator. In the 1940s, diphtheria was out to kill your babies.

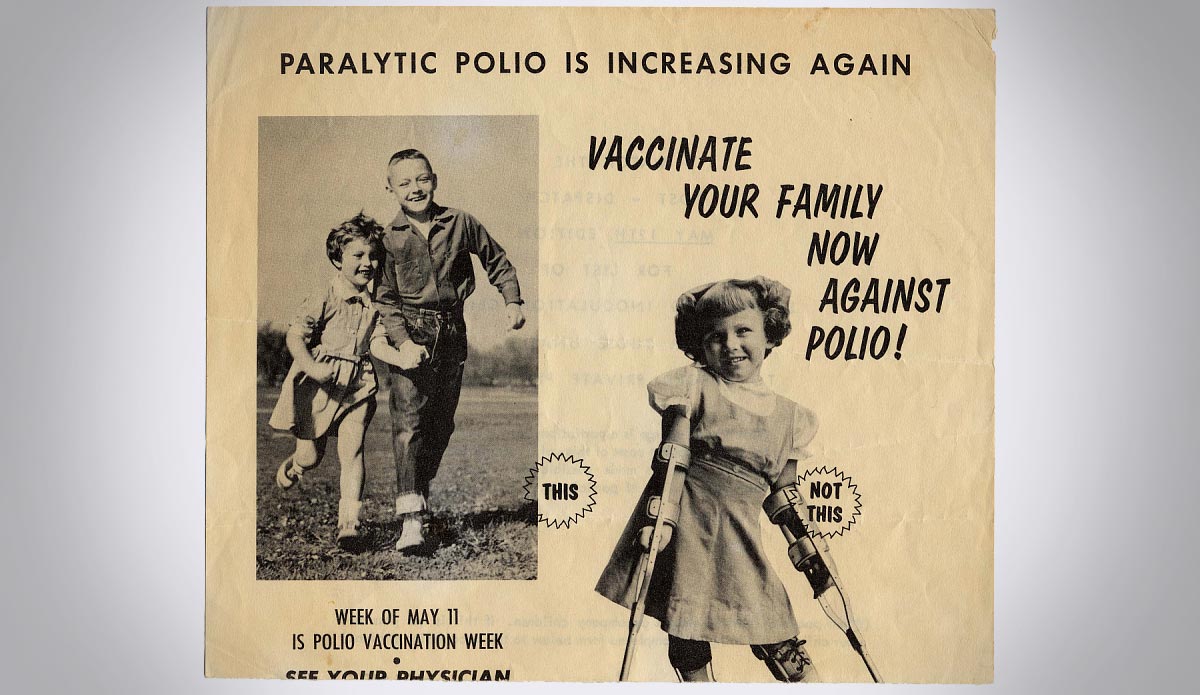

In the 1950s, Polio was coming to paralyze your kids.

In the 1980s, AIDS was equated to a literal apocalypse.1

Were these approaches effective? In some ways, absolutely. Awareness spread. Vaccinations increased. Annual US polio cases dropped from 58,000 in 1957 to only 161 cases in 1961.2 However, studies have shown that scaring people may not be the most effective way to change behavior. People are more likely to take action if the perceived outcome is positive, rather than negative.3

This philosophy has gained traction in recent years, and has been True North’s strategy when tackling our own Public Health campaigns. Below is our work for San Mateo County, which asked us to create a campaign that would bring residents together while encouraging preventive Covid measures. We aimed to instill personal responsibility in each resident while providing positive incentives like the successful reopening of county parks, beaches, and local businesses. The onus was on everyone communally and the method was the carrot, not the fire-and-brimstone stick. The messaging was not that death was coming, but that life could return – if we stuck together.

Lifestyles

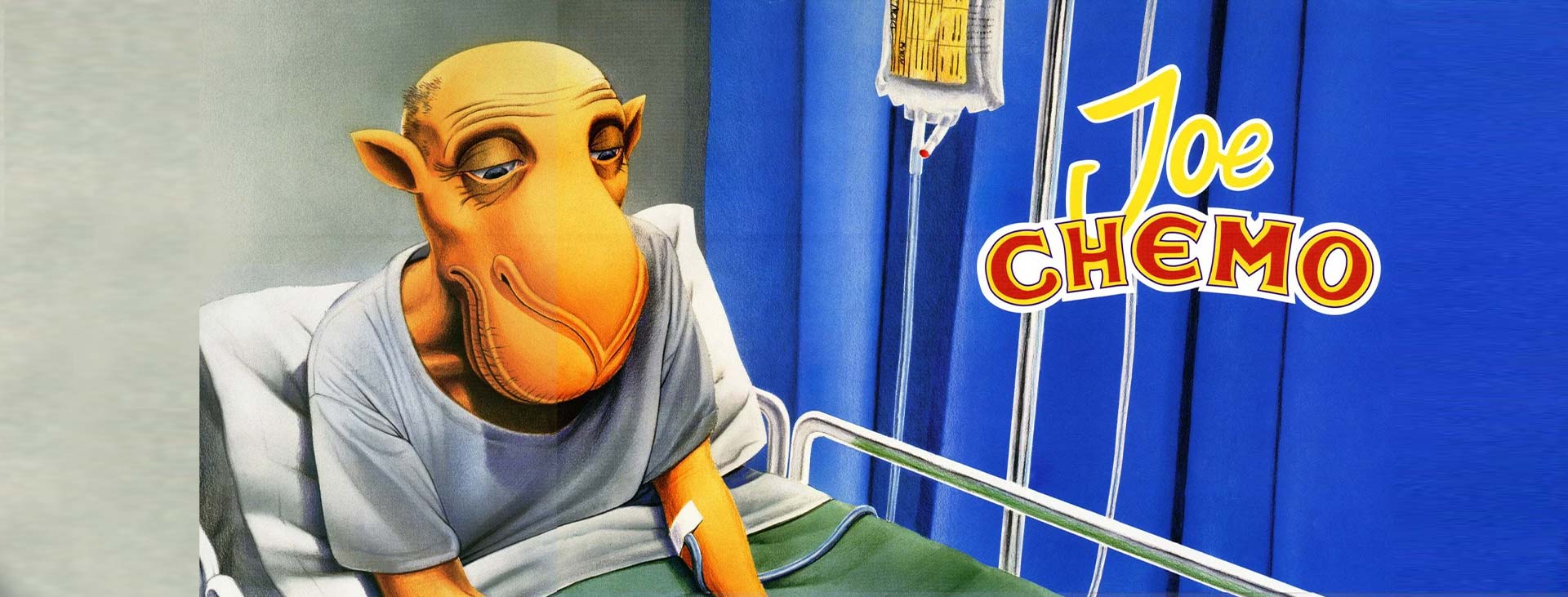

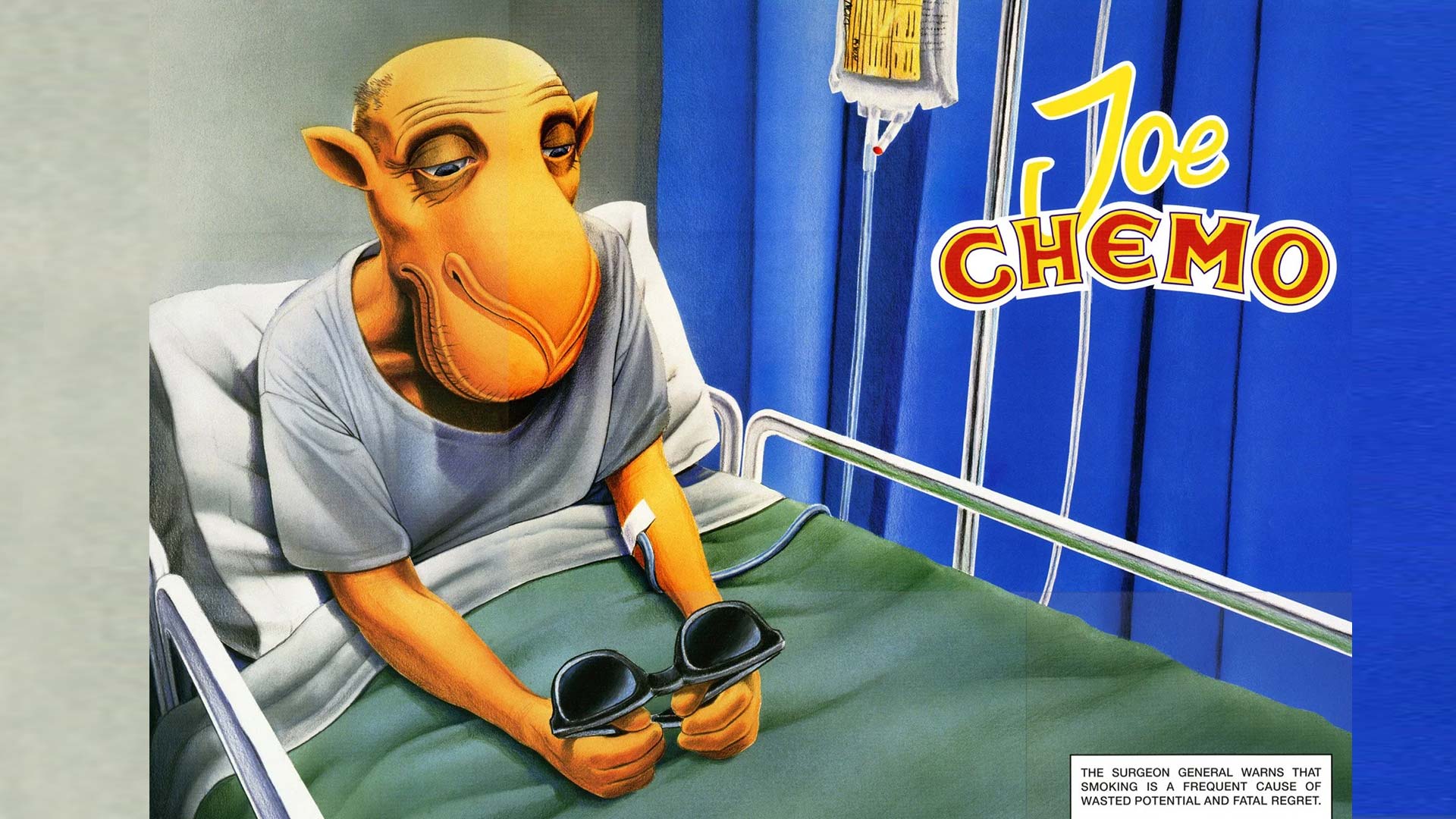

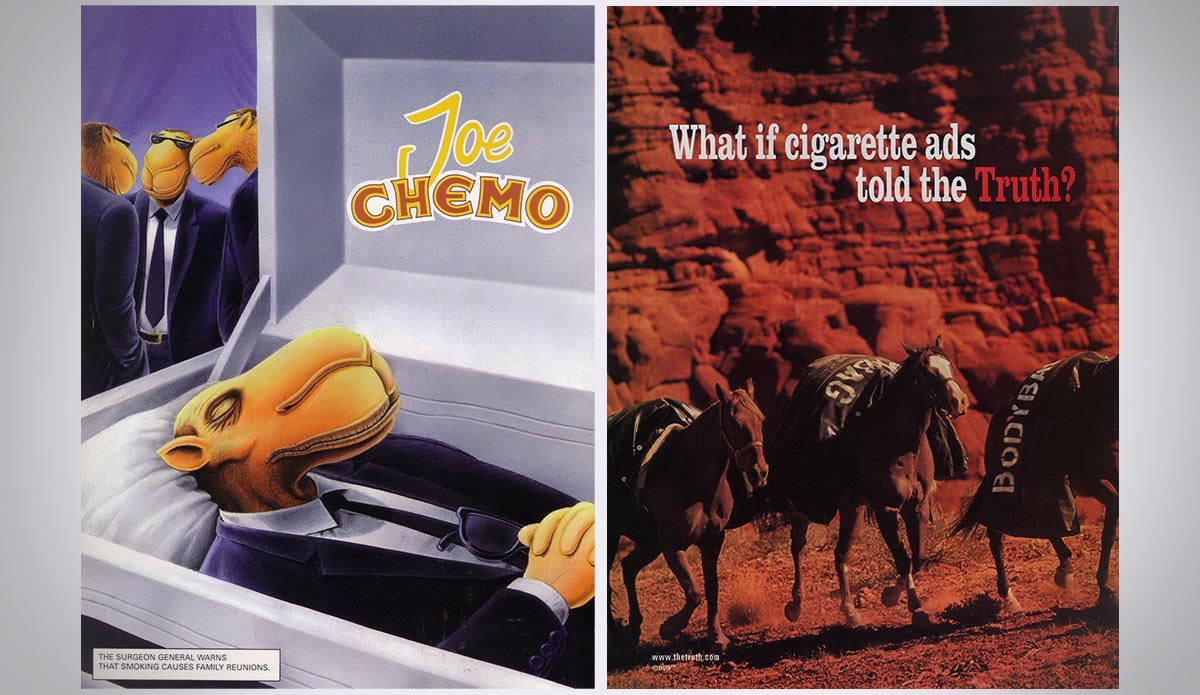

As public health concerns evolved beyond specific diseases, campaigns began to focus on promoting healthy behaviors and lifestyles. Probably the most famous of these were anti-smoking initiatives. Like the aforementioned approach to disease, anti-smoking ads often employed emotionally-charged, sometimes graphic, messaging to evoke fear and danger.

Even child-oriented, lighthearted ads worked on fear. One well-known example was the British anti-smoking advertisement which aired on TVs for the first time in 1980.4 The 30-second clip showed ‘Nick O’Teen’ encouraging a group of kids to smoke. At the last minute, Superman swoops in, thwarts Nick O’Teen, and uses his x-ray vision to reveal the hidden harms of cigarettes inside people’s bodies.

Harm, almost always the focus, eventually spread beyond the individual. Take this German anti-smoking ad, which uses children to highlight the dangers of second-hand smoke. It creates a powerful, albeit strongly negative, emotional response to emphasize the impact of smoking on those beyond the smoker.

Similar methods that focus on mutual responsibility are often used in climate change campaigns, usually in a less devastating tone.

Modern climate campaigns, including our approach at True North, tend to prioritize positive messaging that emphasizes unity and action over fear. For example, in our Break Up with Gas campaign for the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC), we equated toxic gas appliances to toxic exes. Using eye-catching illustrated characters, the campaign encouraged people to prioritize their future, and our planet’s, by breaking with their toxic past. The intent was to empower them to take action, rather than terrorize them into it.

Inclusivity in public health campaigns

One-size-fits-all approaches that miss critical population segments can have serious consequences, especially for public health campaigns. From representation to language, advertisers have been working to overcome this shortcoming.

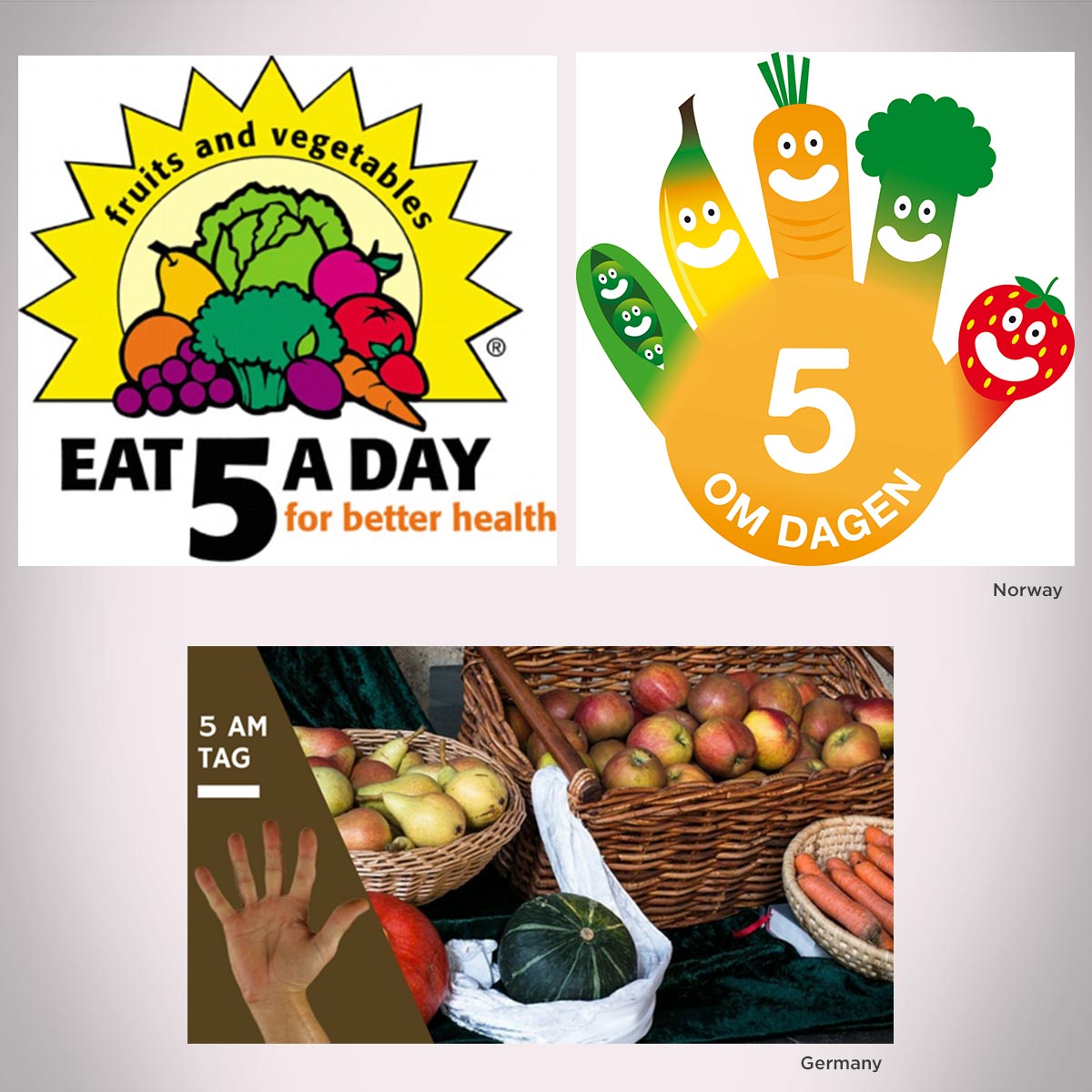

One great early example is the “5 A Day” campaign launched by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in the 1990s.5 The campaign aimed to encourage Americans to consume five or more servings of fruits and vegetables daily. The NCI tailored their messaging to resonate with different cultures by highlighting the use of fruits and vegetables in traditional dishes. The campaign then went global and was translated into an array of world languages.

We aren’t totally sure what Denmark was thinking, but they believed a cheeky edit to “Six a Day” would do the trick.

Our Screen for a Safer Clean campaign grappled with similar hurdles. The campaign, which worked to increase awareness about the importance of screening cleaning products for harmful chemicals, needed to reach diverse San Francisco communities with varied cultures and whose primary languages weren’t English. We solved the problem in two phases.

First, we prioritized the messaging, building awareness using eco-labels and simple, easily understandable language.

Second, we prioritized accessibility. We did so by providing educational materials in multiple languages, using universal symbols to convey information about safe cleaning practices.

However, accessibility meant more than simply translating the words. We needed a campaign that could be “transcreated”, or adapted from one language to another while maintaining the meaning, style, and content. We worked to create something that would be culturally sensitive and linguistically appropriate, but also familiar and powerful across cultures when translated.

What’s Next?

What does all this mean for the future of public health campaigns? Many campaigns will likely continue to encourage people to live healthier lives through collaboration, connection, and empowerment. However, with the constantly evolving landscape of public health, the shape of those campaigns will inevitably change. What will that change look like? One interesting approach, and potential harbinger of things to come, is the move toward a “co-design” methodology of campaign creation where the communities that are the target audience are also the architects. Involving the target audience in the campaign creation process allows for a more personalized approach and more accurate, effective work. As advertising continues to evolve, we think it’s important to embrace these exciting new methodologies that prioritize inclusivity and collaboration.

_________________________

1 https://www.thriveagency.uk/insights/the-evolution-of-public-health-campaigns/

2 https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/history-of-vaccination/history-of-polio-vaccination

3 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11009129/

4 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31857911/

5 https://www.comminit.com/content/5-day-campaign-united-states